Padres: Breaking Barriers

Johnny Baseball

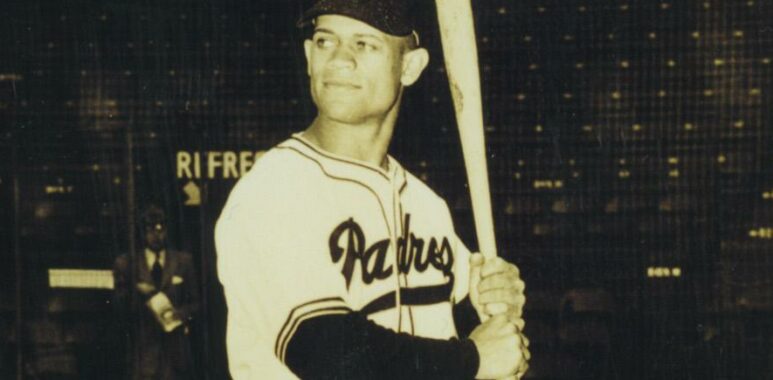

“It was a thrill to play for the Padres. The fans cheered and my feeling was it was because I was a San Diego boy making good. It had nothing to do with race. A lot of friends and family were in the stands at Lane Field. It felt good to get a turn at bat, but I grounded out to the first baseman.”

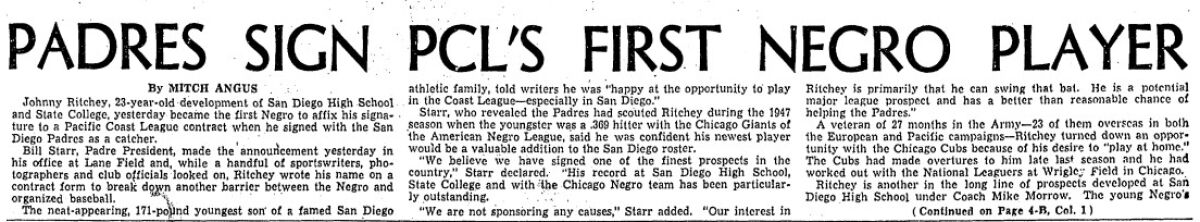

Those are the modest memories of Johnny Ritchey who, 75 years ago, broke the color barrier in the Pacific Coast League. Back then, San Diegans rejoiced that another local was playing for the hometown team. They knew all about the young catcher who had led the Negro American League in the batting the previous year. He was “Johnny Baseball.”

What Ritchey failed to mention in his first memories as a Padre was that he collected seven hits in his first eleven plate appearance. That would be bragging and bragging wasn’t part of his personality. His main point was to relay the thrill of playing ball in his hometown.

John Franklin Ritchey was born in San Diego a century ago on January 5, 1923. His father, William, starred for the earliest local ”colored” team — the 1906 Coast Giants — that primarily played against white teams. His older brother, Bert, was a legendary football player at San Diego High School during the 1920s. He was heavily recruited and selected gridiron powerhouse USC where he unceremoniously sat on the bench. Trojans coach Howard Jones wanted the elder Ritchey so his team wouldn’t have to play against him.

Ritchey’s mother died when he was young, so he was raised along with his younger cousins, Ed Fletcher and Ted Ritchey, by his older sisters, Dallas Frances (Sugar) and Priscilla.

Sports were part of the Ritchey family DNA. His earliest memories were about baseball with his friends. Ritchey played at San Diego High School and was a member of the 1938 Post 6 American Legion National Championship team at age 15. The series was in Spartanburg, S.C., and, because of racial segregation, Ritchey was not allowed to play.

Post 6 again represented the west in the 1940 tournament held in Shelby, N.C. Ritchey broke the color barrier south of the Mason-Dixon line with a game-winning double against St. Louis in the opening game of the series. San Diego would next face Albemarle, N.C., in the championship series … in Albemarle.

Because of their race, Johnny and teammate Nelson Manuel were not be allowed to participate. San Diego narrowly lost the seven-game series.

Ritchey graduated high school in 1941 and played baseball at San Diego State College. Then came the war. He served in both the European and Pacific theaters, earning four battle stars as part of the Army’s combat engineer corps. Ritchey was discharged as a staff sergeant and reenrolled at San Diego State in 1946. At the end of the baseball season, he noted that San Diego State coach Charlie Smith “felt bad when the scouts came and they signed my teammates, but not me. He said it wasn’t fair.”

San Diego’s Walter McCoy pitched for the Chicago American Giants in the Negro Leagues. Ritchey didn’t think he was good enough to play in the Negro Leagues, but McCoy — his childhood friend — convinced him to try out. He promised, “If you don’t make the team, I’ll buy your bus ticket back to San Diego.” McCoy was not known to spend his money foolishly. He knew he’d made a safe bet.

In 1947, the year Jack Robinson broke MLB’s color barrier, Ritchey won the Negro American League batting title with a .369 average. Because Negro League statistics were so incomplete, his average has also been listed as .378, .381 and .386. MLB bestowed major league status to the Negro Leagues in 2020, but their “new” statistics are woefully inadequate. The respected Baseball Research website has his 1947 average at .324. Much more research is required, but accurate numbers will probably never be known.

“We believe we have signed one of the finest prospects in the country,” Padres owner Bill Starr told the San Diego Union in 1947. Ritchey responded with a .323 batting average for the 1948 Padres. He would average .300 during nine minor league seasons. Ritchey wasn’t choosy about which bat he used. He said, “You can hit with all of them.”

Ritchey was always a committed family man. He married a preacher’s daughter, Martina (Lydia to family and friends), and together they raised three children: Johnaa, John, Jr. and Toni. After baseball, Ritchey had a milk route and later drove a delivery truck for Continental Baking. Johnaa remembered with a laugh that she and her siblings were raised on day-old Hostess Twinkies.

When Ritchey died at age 80 in 2003, friends and family sought to honor his memory in the form of a bronze bust created by local sculptor Jon Richetti. Money was raised, but the Padres were reluctant to accept the gift. Though media pressure, the bust was finally unveiled at Petco Park in 2005 … and forgotten.

It wasn’t until the Padres’ new ownership group including Peter and Tom Seidler learned about Ritchey that his history again became relevant. They began the Johnny Ritchey Breaking Barriers Scholarship program in 2020. (Update:The lastest presentation was April 14th, 2023 at San Diego High School that featured Padres announcer Jesse Agler, Centerfielder Trent Grisham, Navy Commander Amy Bauerschmidt and former Padre Billy Bean. A video link to that presentation is pending and will be posted)

Monday night, 10 high school seniors who embody “the characteristics and qualities that Ritchey displayed on and off the field, including the capacity to overcome adversity and break barriers” will be awarded scholarships from the Padres before their home game against the Atlanta Braves.

Significantly, the bronze bust of Johnny Ritchey was moved to a place of prominence last year in the Breitbard Hall of Fame on the main concourse in the Western Metal building at Petco Park.

“Johnny Baseball” would have been pleased.

In 1994, he said: “I always played my best when I was happy and all I ever wanted to do was just play baseball.”

Baseball historian Bill Swank is the leading expert on early San Diego baseball including the Lane Field (1936-1957) Era. He has authored and co-authored six books on San Diego baseball.

Padres to honor Ritchey with pregame ceremony, PCL uniforms

The Padres will honor San Diego high school seniors with scholarships and wear their 1948 Pacific Coast League uniforms on Monday, part of a 75th anniversary celebration of Johnny Ritchey breaking baseball’s color barrier on the West Coast.

The uniforms are identical to what the 1948 Padres wore, and feature a navy blue script with red piping and a navy blue hat with a red “S.” The game-used jerseys will be auctioned off at Padres.com/auctions following the game, with proceeds going to the Johnny Ritchey Scholarship Program.

“We are honored to celebrate Johnny Ritchey during this significant 75th anniversary season,” Padres CEO Erik Greupner said in a news release. “Johnny was a San Diegan whose courage and bravery extended beyond breaking the color barrier to also serving his country during World War II. By wearing our 1948 Pacific Coast League uniforms on Monday night, we will honor Johnny’s legacy and accomplishments, which are a great source of pride for the Padres organization.”

Before the game, the Padres will award 10 scholarships to local high-school seniors during a pregame ceremony. The $10,000 scholarships will be distributed over four years.

APRIL 16, 2023 2:08 PM PT